The link between mental illness, violence and other offending remains an area of controversy. The debate can become polarised around two extremes: that no such link exists or the mentally ill as a group are violent.

Cross (2010) emphasises the continuing influence of representations of madness. These notions are transmitted through a range of popular cultural forms; song, film, TV drama and so. Historically, physical representations of the ‘mad’ emphasise wild hair and physical size as signs of their irrationality and uncontrollability.

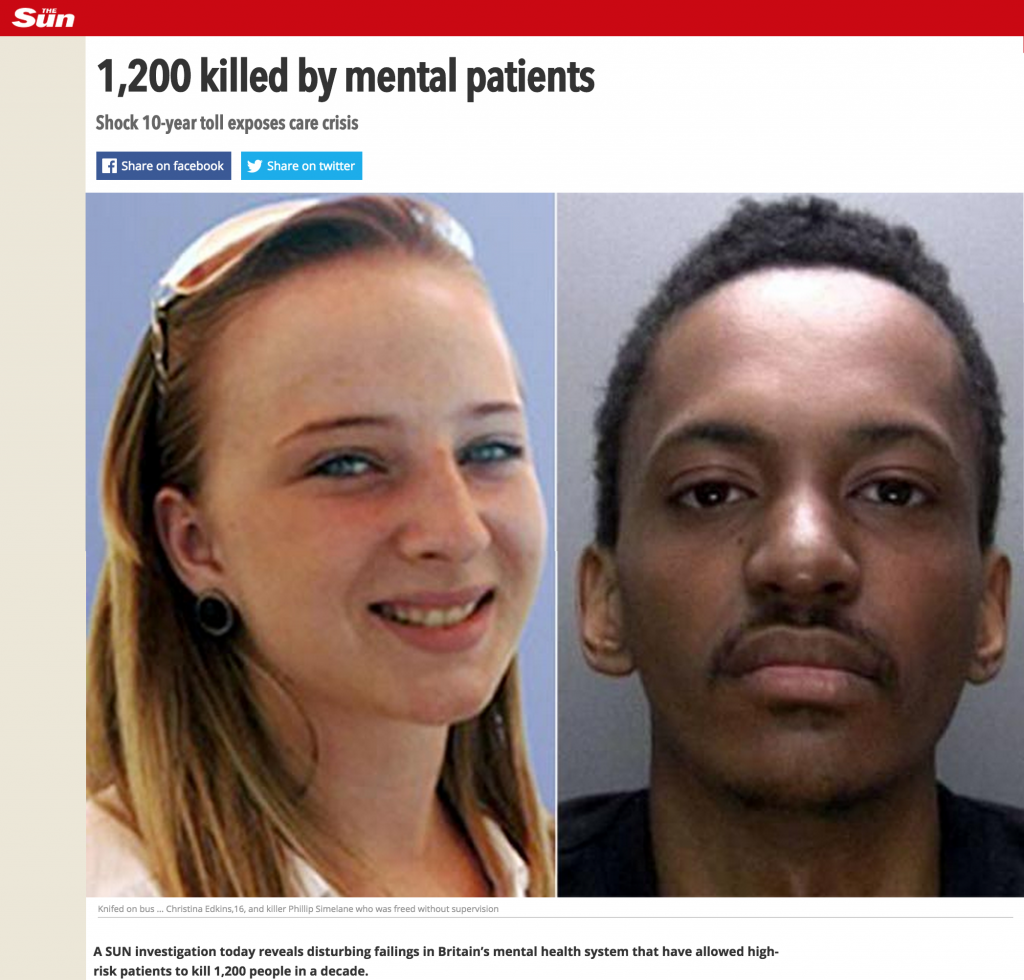

The media portrayal of community care in the 1990s is virtually all based on cases of homicide or serious injury (Cummins, 2010 and 2012). This style of reporting, particularly from the tabloid press was very influential in undermining wider public confidence in mental health services.

This is very much an ongoing issue. For example, last year’s National Confidential Inquiry report showed that in 2010 there were 29 homicides by mentally ill people in 2010, the lowest since 1997 when this data was collected for the first time. This was reported in The Sun in the lurid terms. This sort of atmosphere makes it difficult to examine the research evidence. It is, therefore, vitally important that studies such as this one are not only carried out but the results discussed in a calm, reflective manner.

Background to the study

The increased use of imprisonment

One of the most startling features of social policy development over the past thirty years is the expansion of the use of imprisonment. In the 1970s, criminologists were seriously considering how the prison as an institution was on the verge of disappearing and pondering how it would be replaced as the central penal mechanism in liberal democracies.

There are now over 10 million people in prison worldwide and many more ex-offenders trying to rebuild their lives in the community. The USA leads the way in this penal arms race with over 25% of the world’s prisoners. The prison population is overwhelming male and from poor urban communities. The UK is the European country that has most closely followed the US experience.

As this paper notes, mental health disorders are common in prison populations. A body of research indicates that one in seven prisoners has a psychotic illness or major depressive illness and that one in five newly sentenced prisoners has a substance misuse problem (Fazel et al, 2012). Interventions to tackle these difficulties are not only justified in public health terms but also have the potential to tackle the problems of reoffending.

Research shows that one in seven prisoners has a psychotic illness or major depressive illness.

Methods

There is little research that explores the links between psychosis and violent reoffending. This work is a population based longitudinal study of released prisoners. The study sought to address three broad areas:

- Is psychiatric diagnosis associated with violent offending?

- Are their differing links between violent offending and mental health conditions for different diagnoses?

- What is the impact of comorbid substance use disorder?

The study used data from Sweden where all residents including migrants to the country have a unique personal identifier, which is used across national registers. Researchers are thus able to make data linkage and, in the case of this study, were able to follow a cohort of convicted prisoners who had been imprisoned since 1 January 2000 and released before 31 December 2009.

The individuals were followed from the day of release until they committed a violent crime, death, emigration or the end of the study. Violent crime was defined as homicide, assault, robbery, arson, any sexual offence, illegal threats or intimidation.

Violent crime was defined as homicide, assault, robbery, arson, any sexual offence, illegal threats or intimidation.

Results

The study identified 47,326 prisoners (43,840 males and 3,486 females). The paper itself reports the findings in great and precise detail. There is not the scope to provide all that information here. However, the rigorous analysis of the data is one of the outstanding features of this excellent paper.

- 42% of male prisoners had been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition before their release

- 25% of the male prisoners committed a violent offence during the period of follow-up

- Reflecting the experience of the UK, mental health problems were more common amongst female prisoners. 64% of this cohort had a psychiatric illness but violent reoffending was less common

- 11% of women committed a violent offence during the follow-up period

- Assaults (64%) accounted for the overwhelming majority of the violent reoffending

- Prisoners with a psychiatric history had a higher rate of reoffending. They were also likely to reoffend earlier than those who had no psychiatric history

- The authors concluded that 2,187 out of 10,884 violent offences committed by men after release could potentially be the result of psychiatric disorder

- For women, the figure was 152 out of 379 offences

- In exploring individual diagnoses and possible links with violent reoffending, the association was increased for all diagnoses. The strongest links were for

- Alcohol and drug use

- Bipolar disorder

- Personality disorder

- ADHD

- Other development and conduct disorders

- Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

Assuming causality, up to 20% of violent reoffending in men and 40% in women was attributable to the diagnosed psychiatric disorders investigated.

Discussion

This is a study that is tackling a very complex issue. Violent offending behaviour is a classic example of a phenomenon that is multifactorial. The pattern of interactions between these factors is often difficult to identify or explain in a straightforward linear causal fashion.

The study is limited to Sweden; a country that has much lower levels of violent crime than other industrial societies. There are always problems with the recording of offences. It is well established that certain types of crime, particularly sexual violence against women and children is under reported. This study is based on conviction rates.

In addition, the categorising of offences raises questions. For example, the majority of offences here are for assault. This can cover a very wide range of offences. There is no information provided about the victims of these offences. This is a very important piece of the jigsaw and an area for further exploration. For example, what are the sorts of social circumstances in which this violence occurs? Does it take place within families or intimate relationships?

Allowing for all of the above, this is a fascinating piece of work. It will force many professionals who work in mental health to think again about these issues. The authors are asking us to approach the issue of mental health and reoffending in a calm logical fashion rather than the lurid tones in which this debate is usually conducted.

Are we ready to discuss mental health and violent reoffending in a calm and logical manner?

The researchers have had access to a vast range of data that enables them to track individuals over a long period. This study shows that as the authors put it:

Psychiatric disorders were associated with a substantially increased hazard of violent reoffending.

This was independent of other sociodemographic, criminological and family factors.

This paper can be read as a statistical argument about the linkage of violent offending and psychiatric disorder. Others are far more qualified than I am to discuss those aspects. I read it as providing a strong argument for greater investment in mental health services and prison services in particular. This can be justified in terms of both the individual health of offenders but also wider public safety and a reduction in violent offences. It is the ethical thing to do, but it is also in the wider interests of society. The impact of violent crime spreads like ripples through the lives of victims, families, future generations and as is often not readily acknowledged offenders.

The overlap between mental health and the criminal justice system is a well-established one. Many people with mental health problems move between the two or are homeless. As the authors conclude:

Our findings underscore the need for improved detection, treatment and management of prisoners with mental health disorders and the linkage of these prisoners to community-based mental health services on release.

These are sentiments that all those working in mental health and criminal justice system would support. The challenge is how to provide services that engage with the most vulnerable people in the most effective fashion. A challenge that is made all the more difficult by the current climate of austerity.

Anyone with an interest in these areas should read this paper.

This new evidence strongly supports calls for better screening and mental health services for prisoners, to prevent future violence and improve public health and safety.

Links

Primary paper

Chang Z, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Fazel S. (2015) Psychiatric disorders and violent reoffending: a national cohort study of convicted prisoners in Sweden (PDF). Lancet Psychiatry 2015 Published Online September 3, 2015.

Other references

Cross, S. (2010). Mediating Madness: Mental Distress and Cultural Representation. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cummins ID. (2011) ‘Deinstitutionalisation; Mental health services in the Age of Neo-liberalism‘, Social Policy and Social Work in Transition.

Cummins ID. (2010) ‘Distant Voices Still Lives: reflections on the impact of media reporting of the cases of Christopher Clunis and Ben Silcock‘ Ethnicity and Inequalities in Health and Social Care 3 (4), pp. 18-29.

Fazel S, Seewald K. (2012) Severe mental illness in 33,588 prisoners worldwide: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2012; 200: 364–73.

Important paper by @seenafazel et al http://t.co/LLj81vPTr0 @IanCummins9

Common mental health disorders linked with increased risk of violent… http://t.co/1GHcU1sshk #MentalHealth http://t.co/RCggRTZBFA

@Mental_Elf Nice account of paper. Not true though that violent crime rates are “much lower” in Sweden.

@Mental_Elf clear and thoughtful summary. Also compared prisoners with mental disorders with their siblings in prison without disorders 1/2

@Mental_Elf which is a powerful way to account for residual confounds (esp genetics and early environmental factors) 2/2

@Mental_Elf @TheLancetPsych #brainwashequipment used on #LGBT people by #Royalfamily member UK causing depression Plse RT

@Mental_Elf waiting to see which party notices need to improve #mentalhealth care in federal prisons @Carolyn_Bennett @JustinTrudeau

Today @IanCummins9 on @LancetPsych @seenafazel study of psychiatric disorders & violent reoffending http://t.co/rdurvRD9AT

Cohort study finds psychiatric disorders were associated with a substantially increased hazard of violent reoffending http://t.co/rdurvRD9AT

@121Therapy: Common mental health disorders linked with increased risk of violent reoffending in ex-prisoners https://t.co/m6wHpIotfV

Very interesting again. Thanks mental elf

Don’t miss: Common mental health disorders linked with increased risk of violent reoffending in ex-prisoners http://t.co/rdurvRD9AT #EBP

Keep Calm & Discuss Violence: Any link between mental health & violent offending is complicated & poss. non-causal https://t.co/UB5uMVNz48

RT @Mental_Elf: New cohort study strongly supports calls for better screening and mental health services for prisoners http://t.co/bL5ad0VP…

RT @Mental_Elf: Are we ready to discuss mental health and violent reoffending in a calm and logical manner? http://t.co/rawiwbaAqi http://t…

Common mental health disorders linked with increased risk of violent reoffending in ex-prisoners https://t.co/onIUzeAxTV via @Mental_Elf

Common mental health disorders linked with increased risk of violent reoffending in ex-prisoners https://t.co/OlV6JmHz9m @peter_g_miller