Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most of us have experienced separation from our loved ones, with an uncertainty of when we will see them again. This isolation from family members has understandably seen deterioration in wellbeing, disruption of mood and increased levels of anxiety in a lot of us (Gloster et al., 2020; Panchal et al., 2021).

Family separation has always been commonplace in refugee communities, with immigration policies often resulting in forced displacement and families being separated across countries with little information on possible reunion (Okhovat et al., 2017). Much like pandemic-related social isolation, this separation can result in elevated symptoms in numerous mental health disorders and reduced quality of life (Miller et al., 2018).

Whilst seemingly an obvious question, it is important to consider the ‘why?’. Why does family separation often result in worsened mental health outcomes in this group compared to those who sought refuge with their loved ones? While social, economic and cultural factors have previously been implicated in this relationship (Oxfam and Refugee Council UK, 2018), the importance of each had not been considered until a recent paper by Liddell and colleagues (2021).

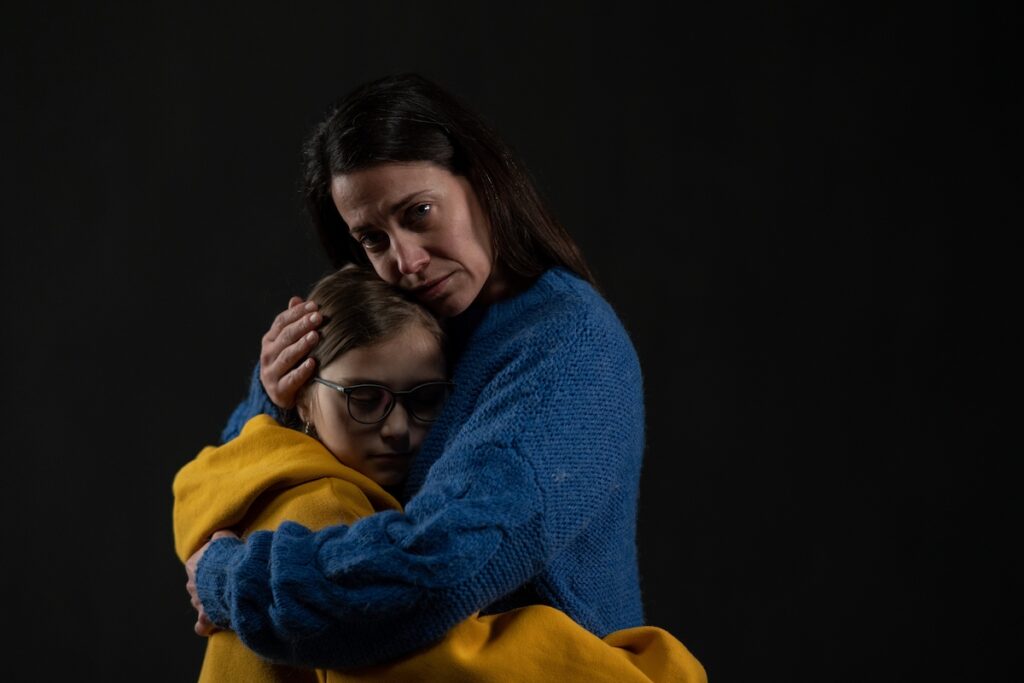

Being away from loved ones has affected everyone during the pandemic, but refugees often experience family separation for an extended period of time.

Methods

1,083 Australian settled refugees participated in the study. Individuals were recruited through numerous pathways such as targeted social media, refugee-specific services, and snowballing. Each participant was asked to complete a battery of questionnaires.

Key data collected included:

- Current family status, denoted as either ‘no immediate family in Australia’ or ‘some/all immediate family in Australia’;

- PTSD symptoms using the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale, depression symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire, and daily functioning using the World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule;

- Post-migration living difficulties (PMLDs) over the past 12 months using the PMLD checklist. Difficulties were categorised as:

- ‘social’ e.g., isolation and discrimination,

- ‘economic’ e.g., employment and being financially comfortable,

- ‘fear for future’ e.g., status in Australia, and

- ‘fear for family’ e.g., safety;

- Collectivist or individualist identity using the Self-Construal Scale (SCS);

- Demographic variables such as age, sex, marital status, physical health, and employment; and

- Lifetime exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs), such as conflict or torture, using the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire.

Results

Separated vs non-separated group differences

Researchers looked to identify group differences between refugees labelled as ‘separated’ (N=247) and ‘non-separated’ (N=814) from their families. The separated group, compared to the non-separated group, were more likely to:

- Be younger, Farsi-, Tamil- or English-, single, male, and childless;

- Have been exposed to each event on the PTE, with almost double the number cumulatively;

- Have PMLDs elevated in each category;

- Have higher depression and PTSD symptoms.

Family separation predicted both depression and PTSD symptoms over and above demographic variables such as age, gender, and PTE exposure. However, since no differences were reported in daily functioning or collectivist self-identity, separation did not uniquely predict disability symptoms or cultural background.

The ‘why’

To identify why the separated group had worse mental health outcomes the researchers split the sample by separation status to identify significant relationships between mental health outcomes and the other key variables by group. Analysis suggested that the model for each group was significantly different. For the separated group:

- Higher PTE levels were directly related to depression and daily functioning.

- Increased PTE levels were indirectly related to higher depression via social and economic PMLDs, PTSD via social and fear for the future PMLDs, and lower daily functioning via social PMLDs.

- Collectivism was directly related to increased PTSD and depression.

- High collectivism levels were indirectly related to increased depression and PTSD and lower daily functioning via elevated social PMLDs.

- Female sex was directly associated with lower daily functioning.

- Age showed no direct effect.

For the non-separated group:

- Increased PTE levels were directly associated with increased depression and PTSD, and decreased daily functioning.

- Elevated PTE levels were indirectly related to increased depression and PTSD and lower daily functioning via social and fear for the future PMLDs.

- Collectivism was directly related to depression.

- Increased collectivism was indirectly related to elevated depression via higher economic PMLDS.

- Female sex was directly associated with depression and PTSD.

- Older age was directly related to lower daily functioning.

Refugees that settled with their family members showed better mental health outcomes compared to their separated from family counterparts.

Conclusions

Overall, refugees separated from their families experience worse mental health outcomes, with higher levels of depression and PTSD symptoms compared to their non-separated counterparts; a relationship that sustains even when controlling for PTE exposure and demographics. A specific driver of these poorer mental health outcomes was revealed to be collectivism.

Family separation among refugees was associated with worse mental health outcomes, and higher levels of depression and PTSD.

Strengths and limitations

Identifying and filling a research gap is key to creating novel and significant literature. Liddell and colleagues (2021) build on previous work that looks at differences in mental health outcomes between separated and unseparated refugees and shed new light on this topic.

While the study’s sample is large and diverse, with over 1,000 participants across genders, ages, marital/parental status, and language, it cannot be taken as representative of all refugees. Snowballing means that individuals from particular social groups or post-settled locations may be over-represented. This needs to be considered when evaluating the study’s results, as outcomes may only be applicable to these groups or Australia. Other countries and areas may vary in their treatment, provisions and settlement policies regarding refugees and their movements.

Little is known about participants experience prior to completion of the questionnaire battery, both in their home and settled country. Whilst the study collected PTEs, the timepoint of these events is not documented. Knowing more about the individual’s experiences and the timing of events would help create a richer image of the relationship between separation and mental health outcomes as well as help remove potential confounders.

The potential for confounding must also be considered when looking at the measure of separation. Whilst creating a dichotomous variable allowed ease of analysis, separation status is more than a yes/no question in many incidences. For example, participants may have had extended, rather than immediate family with them, which, given the high rates of collectivism, will have had an impact. Little is also known about the nature of the separation, whether it is forced, how long the individuals have been separated, where the families are, and the level of contact.

Participants were solely individuals seeking refuge in Australia, so the findings may not be representative of refugee populations around the world.

Implications for practice

It is important to consider what these results mean for refugees, both separated and unseparated from their families. Steps can be taken to identify those most at risk and recognise ways in which to help them most effectively.

Firstly, this data provides clear evidence that settlement away from families has a negative impact on an individual’s mental health, and where possible, refugees should be homed with family members. Settlement policies should provide greater consideration of this when assessing refugee status, and countries should, in theory, be working to home family members together where possible. Removing individuals from areas of physical danger should continue to be the top priority, but mental wellbeing of these individuals should also be a concern, and family settlement may well be a step in the right direction.

Social stressors are also a key future focus when working with refugees. Isolation, discrimination, and loneliness were linked to poorer mental health outcomes, particularly in those separated from family members. More action needs to be taken to help reduce these social stressors. For example, on settlement, refugees should be directed to social support groups whom they can rely on, even when away from family members. Further, these results suggest that a collectivist self-identity may be a barrier to refugees ‘socially settling’ in their host countries. Collaborations between refugee groups and host nations to provide education on these differing collectivist/individualist self-identities would be beneficial. This teaching should help reduce social stressors in refugees by creating greater shared cultural awareness and understanding (Bernardi et al., 2019). Lastly, consistent with the literature, all refugees had high levels of PTEs. The experience of torture, sexual violence and witnessing the murder of a loved one were commonly reported in participants. The host countries should prioritise the provision of trauma-informed psychological services for individuals.

The hardships that refugees experience are something that we, the public, will likely never understand. Now, more than ever, we can empathise with the experience of being separated from loved ones for an indeterminate amount of time. So, the results and implications of this paper should be heavily valued and considered.

Encouraging a shared social awareness and understanding may improve mental health outcomes for refugees.

Statements of interest

None to declare.

Links

Primary Paper

Liddell, B. J., Byrow, Y., O’Donnell, et al. (2021). Mechanisms underlying the mental health impact of family separation on resettled refugees. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 55(7) 699-710.

Other references

Bernardi, J., Engelbrecht, A., & Jobson, L. (2019) The impact of culture on cognitive appraisals: Implications for the development, maintenance, and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychologist 23 91–102.

Gloster, A. T., Lamnisos, D., Lubenko, J., et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: An international study. PloS one 15(12), e0244809.

Miller, A., Hess, J. M., Bybee, D., et al. (2018) Understanding the mental health consequences of family separation for refugees: Implications for policy and practice. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 88 26–37.

Okhovat, S., Hirsch, A., Hoang, K., et al. (2017) Rethinking resettlement and family reunion in Australia. Alternative Law Journal 42 273–278.

Oxfam and Refugee Council UK (2018) Safe but not settled: The impact of family separation on refugees in the UK.

Panchal, U., Salazar de Pablo, G., Franco, M., et al. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. European child & adolescent psychiatry 1-27.

Photo credits

- Photo by Joey Csunyo on Unsplash

- Photo by Ricardo Gomez Angel on Unsplash