The creation of the NHS precipitated a community care approach in mental health treatment. It led researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to emphasise the role of social factors such as employment and family in understanding and treating various illnesses. In research, “social networks” have been conceptualised to outline personal networks and shared values that promote feelings of community and well-being in individuals (Palumbo et al., 2015).

Today, social networks help individuals with severe mental illnesses (SMI), who typically have fewer and lower quality social support, discover social factors important to them (Brunt & Hansson, 2002).

A recent study by Sweet et al. (2017) explored the interaction between social ties, places, and activities with the aim of understanding the influence of social networks on the well-being of individuals with SMI.

Social networks play a key role in well-being in severe mental illness.

Methods

The researchers collected descriptive data over 30-months from two locations in England. Quality Outcome Framework (QOF) registers were used to contact, identify and interview eligible participants (16-65 years, English-speaking, primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or other psychoses, and recipients of primary/secondary care for at least two years).

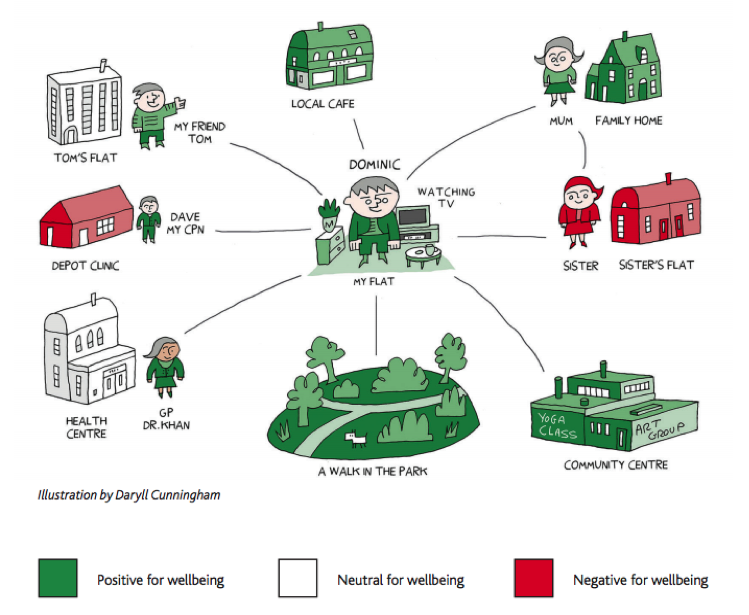

A personal well-being network (PWN) mapping tool was created to map participants’ social ties, meaningful activities/hobbies and connections to places. Additionally, participants drew closeness maps to demonstrate their most significant emotional ties. Participants were measured on mental well-being, social capital, current physical health and social functioning.

Results

The results indicated three types of personal well-being networks (PWNs):

- Formal and sparse (31.3%) – indicative of fewer social ties and engagement in less meaningful activities. Participants in this network had the most contact with secondary care.

- Family and stable (32%) – indicative of access to most social support from friends and family. Participants in this network engaged in many meaningful activities, had many community place connections and engaged the most with primary care services.

- Diverse and active (36.7%) – indicative of more socially diverse ties. Participants in this network spent the most time engaging in meaningful activities, social activities and community places.

The formal and sparse network scored lowest in mental well-being and overall health self-ratings. Conversely, the diverse and active network scored the highest in these tests, as well as received a higher proportion of social capital. The family and stable network scored between the two. There was no significant difference found between the networks when measuring quality of life.

As you would expect, the formal and sparse network scored lowest in mental well-being and overall health self-ratings.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that:

Place locations and meaningful activities are important aspects of people’s social worlds. PWNs have important implications for person-centred recovery approaches through providing a broader understanding of individual’s lives and resources.

Strengths and limitations

This study looks through a biopsychosocial lens and focuses its attention on the often abandoned social aspect of recovery. Social participation and community connections are influential in promoting well-being, particularly during the course of SMI (Pinfold & Sweet, 2015). The findings of this study are also valuable as they challenge current assumptions that equate SMI with reclusion, lack of social contact and loneliness.

Clinically, it is found that practitioners fail to encourage individuals with SMI to engage in new and diverse community activities. This is usually initiated by the individual themselves or their families. Thus, this new evidence shows the value of developing targets for social intervention at the clinical level, which involve places and activities. It promotes an individualised, person-centred approach to recovery.

Despite the strengths of the paper, there were several limitations:

- The sample was unrepresentative of the general population due to a high concentration of Caucasian participants. Taking ethnicity into consideration is particularly important when examining social networks as cultural differences lead to differences in how we manages our illnesses. For instance, Asian Americans are less likely to use social support during stressful times as compared to White Americans (Taylor et al., 2004). Hence, cultural attitudes about SMI could influence the social network maps and associations in this study.

- The study was inconclusive in determining the generalizability of the three network types across different samples. This questions the value of creating network types beyond the scope of the study and using them as effective tools for social intervention.

- The person-centred approach of creating individual PWNs within clinical settings is an intervention that should be heralded. However, the name-generator approach, a method of generating names of each individual in a PWN, is a time-intensive and costly process. Is it then safe to assume it is feasible in clinical settings?

Are personal well-being networks viable in busy clinical settings?

Implications for practice

PWN mapping can help identify social connections, places and activities paramount to well-being. Recognising weaknesses in our social networks allows practitioners to intervene at the right place and right time, and accelerate the recovery process in individuals with SMI. Furthermore, it inspires personalised treatment plans by focussing on the social goals of the patient rather than forcing community approaches not conducive to a patient’s objective.

Despite significant findings associated with poor social networks in SMI (Perese & Wolf, 2005), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has not endorsed the development of social networks. Although charities are working towards this goal (McGowan and Jowett, 2003), implementing standardized tools such as PWN mapping on a national level will encourage the development of social networks in clinical practice.

Mapping can also be used to identify priority groups for interventions and also help patients understand the development of their connections, their decisions regarding these connections and various pathways of social dialog. For instance, the researchers found through mapping that patients who relied heavily on practitioners had fewer social resources – possibly due to small network type, place connections, and lack of engagement in meaningful activities. This highlights the efficiency of PWNs in identifying key aspects of change and allows practitioners to intervene through person-centred care.

Finally, PWN mapping can be used as a framework for patients moving from secondary to primary care. Education regarding self-care and help-seeking would allow individuals to successfully integrate in a community environment. This is vital in long-term management of SMI and helps reduce likelihood of relapse.

Future research should investigate the longitudinal impact of social networks through follow-up with patients using PWNs to integrate into society. This would help improve the quality of social interventions and reduce the social and financial burdens associated with secondary care interventions.

It is not news to many that a lack of significant social ties can make us feel lonely and isolated. Individuals with SMI are grossly challenged with multiple difficulties and find it particularly hard to form social ties, which in turn hamper their recovery. Acknowledging these impediments and intervening with PWN mapping can help assimilate these individuals in a meaningful manner in our society.

Personal well-being network mapping is an intervention with clinical potential in patients with severe mental illness.

Contributors

Thanks to the UCL Mental Health MSc students who wrote this blog: Devishi Bhartia, Ana Dumitru, Vanessa Haugaard, Maria Hernandez, Jessica Lynch, Ross Nedoma, Yilin Wang, Pascal Michael, Shashya Wijesinghe, Katerina Papagavriel and Mimi Suzuki. Great work everyone!

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Links

Primary paper

Sweet, D., Byng, R., Webber, M., Enki, D. G., Porter, I., Larsen, J., Huxley, P., & Pinfold, V. (2017). Personal well-being networks, social capital and severe mental illness: exploratory study (PDF). The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1-10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.203950

Pinfold V, Sweet D, Porter I, et al. (2015) Improving community health networks for people with severe mental illness: a case study investigation. Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 3.5. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015 Feb.

Other references

Brunt, D., & Hansson, S. (2002). The social networks of persons with severe mental illness in in-patient settings and supported community settings. Journal of Mental Health, 11(6), 611-621. [Abstract]

McGowan, B., & Jowett, C. (2003). Promoting positive mental health through befriending. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 5(2), 12-24. [Abstract]

Palumbo, C., Volpe, U., Matanov, A., Priebe, S., & Giacco, D. (2015). Social networks of patients with psychosis: a systematic review. BMC Research Notes, 8, 560.

Perese, E. F., & Wolf, M. (2005). Combating loneliness among persons with severe mental illness: social network interventions’ characteristics, effectiveness, and applicability. Issues in mental health nursing, 26(6), 591-609. [Abstract]

Pinfold, V. and Sweet, D. (2015). Wellbeing networks and asset mapping. Retrieved from http://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/Our-briefing-paper.pdf

Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Kim, H. S., Jarcho, J., Takagi, K., & Dunagan, M. S. (2004). Culture and social support: who seeks it and why? (PDF) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 354.

Photo credits

- By Terry (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

- http://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/Our-briefing-paper.pdf

- Photo by Štefan Štefančík on Unsplash

- Photo by Pedro Gabriel Miziara on Unsplash

- Alan O’Rourke CC BY 2.0

[…] people with mental health problems regularly feel lonely and isolated (Perese & Wolf, 2005). A recent Mental Elf blog highlighting research by Sweet et al., (2017) further highlights the importance of social […]