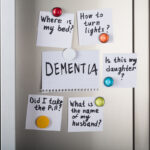

55 million people worldwide are living with dementia. In the UK alone, that is 900,000 people. Depending on the stage and type of dementia, someone with the condition can experience different behavioural symptoms. These include agitation, aggression, sleep problems, eating habit changes, or hallucinations.

When we talk about dementia, many people think about memory problems or difficulties in doing everyday activities, such as cooking or getting dressed. And yes, these are key symptoms of dementia, which vary in severity and type by the different dementia subtypes (Giebel et al., 2020; Perry & Hodges, 2000).

What most people don’t necessarily associate with dementia are hallucinations though. They are less common than problems with cognition, such as forgetting what you’ve had for dinner or the last time you went to the shops, or how to pay for something. There are different types of hallucinations – auditory and visual – in simple terms this means hearing or seeing things that are not really there. The former happens in up to 12% of people living with dementia (Bassiony & Lyketsos, 2003), and in even more with Lewy Body dementia – up to 31% (Eversfield & Orton, 2018). If we think about experiencing auditory hallucinations (hearing one or more voices that are not really speaking), this can be pretty daunting. So how are they linked to well-being in people living with dementia?

In this blog, I am looking at a recent study from the IDEAL (Improving the Experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life) programme, which looked at the impact of auditory hallucinations on living well with dementia in the community (Choi et al., 2021).

12% of people living with dementia may experience visual or auditory hallucinations that can affect their wellbeing. What is the impact of auditory hallucinations on living well with dementia in the community?

Methods

Before I dive into the methods of this particular paper and analysis, let’s introduce the IDEAL programme first. The IDEAL study is a longitudinal cohort study across three nations – England, Wales, and Scotland, exploring social, psychological, and economic factors that may improve the ability to live well with dementia. The study team started collecting data between June 2014 and August 2016, from a whopping 1,540 community-dwelling people with dementia and 1,278 unpaid carers.

People with dementia had a clinical diagnosis of dementia and were in the mild to moderate stages of the condition. This was measured by scoring 15 or higher on the Mini-Mental State examination (which has a maximum score of 30, and higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning).

Back in those pre-pandemic days, researchers collected data by visiting the person with dementia and carer at their home, with participants completing questionnaires and other measures separately.

For this particular paper, the authors used that baseline data, focusing on auditory hallucinations as measured via the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (which contains one question about auditory hallucinations). Living well was measured using three validated tools – the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD), the World Health Organization Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5), and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SwLS). Data on cognition, people with dementia depression, and carer stress, as well as demographic data, were also included in the analysis.

In terms of analysis, the authors first used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to look for statistical differences between those people with dementia who did experience auditory hallucinations and those who did not. Then, they used Analysis of Covariance (or ANCOVA) to also look for any confounding effects of cognition, depression, carers stress, and antipsychotic drug prescription.

Results

Their overall sample included 1,251 people with dementia and their unpaid carers. In terms of whether auditory hallucinations were associated with poorer quality of life and well-being, they were significantly indeed on all three measures. When controlling for potential confounding factors, such as cognition, caregiver stress, and antipsychotic medication, the relationship between the presence of auditory hallucinations and poorer well-being remained significant, except for life satisfaction.

The researchers identified links between auditory hallucinations and poorer quality of life and wellbeing despite socio-demographic factors.

Conclusions

Auditory hallucinations are linked to poorer well-being in dementia. This suggests that these hallucinations need to be minimised as much as possible to enable the person with dementia to live well. Under Implications for Practice, I have highlighted a potential pathway for this.

The associations between auditory hallucinations in dementia and poor wellbeing highlights the need to minimise the impact and find ways to increase their quality of life.

Strengths and limitations

The study benefitted from a large baseline sample of their IDEAL cohort, and from having collected data from both people with dementia and their unpaid carers. Collecting data from both however meant that the stage of dementia under investigation was restricted to mild and moderate dementia, leaving out the more severe stage of the condition. This is relevant as behavioural symptoms, such as auditory hallucinations, increase in the more advanced stage of the condition. However, finding these significant relationships with well-being in the mild to moderate stages already indicates that this is very likely to be the case for severe dementia also.

Looking at dementia more specifically as well, the authors do report on different subtype prevalence of the participant sample, including Lewy Body and vascular dementia. They also report in the Discussion on the higher prevalence of auditory hallucinations in Lewy Body and Parkinson’s disease dementia. They do not though report on this in the actual Results. There is no mention of variations amongst dementia subtypes, and it would have been good to see more of that, possibly even including dementia subtype as a covariate.

The study focused on mild to moderate dementia, leaving some questions around the impact on wellbeing among people with severe presentations unanswered.

Implications for practice

As the study showed, experiencing auditory hallucinations was linked to poorer well-being in dementia. This suggests that auditory hallucinations should be targeted by appropriate treatments when aiming to improve well-being in people living with the condition.

There appears to be a growing evidence base on using virtual reality-based therapy in schizophrenia for example to treat auditory hallucinations (i.e., du Sert et al., 2018). This may be a possible avenue, whilst it is important to consider that people with dementia may struggle with virtual reality and digital interfaces for treatments, so non-VR therapy may be best. What this highlights though is that effective treatments from other conditions should be considered for addressing hallucinations in dementia, particularly to avoid an over-reliance on antipsychotics and medication in general.

Overall, when caring for someone with dementia, be that professionally or in an unpaid capacity, people should be aware of the link between hallucinations and poor well-being. By being mindful of this link, a more person-centered approach to supporting someone’s quality of life can be provided.

Clinicians need person-centred approaches to target auditory hallucinations and to support the individual to maintain their quality of life.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Choi A, Ballard C, Martyr A, et al. The impact of auditory hallucinations on ‘living well’ with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL programme. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2021;36(9):1370-1377.

Other references

Bassiony MM, Lyketsos CG. Delusions and hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease: review of the brain decade. Psychosomatics 2003;44(5):388-401.

Du Sert OP, Potvin S, Lipp O, et al. Virtual reality therapy for refractory auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: A pilot clinical trial. Schizophrenia Research 2018;197:176-181.

Eversfield CL, Orton LD. Auditory and visual hallucination prevalence in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 2018;49(14):2342-2353.

Giebel C, Knopman D, Mioshi E, Khondoker M. Distinguishing frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease through everyday function profiles: Trajectories of change. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2021;34(1):66-75.

Perry RJ, Hodges JR. Differentiating frontal and temporal variant frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2000;54(12):2277-2284.

Correlation is not causation. Contrary to the title of this study, the cross-sectional, correlational design does not support conclusions about the purported negative impact of auditory hallucinations on quality of life (QoL) and well-being (WB) among patients with dementia. Auditory hallucinations could be the result (symptomatic) of poor QoL and WB. There could be a reciprocal causal relationship or a spurious (not causal) relationship between these two sets of factors. Study authors seem to think that targeting auditory hallucinations will improve QoL and WB; isn’t it also possible that targeting QoL and WB (more generally) could reduct hallucinations?