Bipolar Affective Disorder is an enduring mental illness that is known to affect 1-2% of the global population and is associated with a poor prognosis if left untreated (Goodwin et al, 2007). Whilst a wide range of drug treatments are available, research has shown that lithium is still considered the most effective treatment for recurrent episodes. Since 2014, NICE guidelines have recommended lithium as first line treatment (Kendall et al, 2014; NICE, 2014).

Despite NICE advice, it’s often argued that lithium is under-prescribed in clinical practice in the UK. Data on the prescribing of lithium for bipolar disorder has been studied in other European countries, which demonstrates a declining trend. In Denmark, prescription data for bipolar disorder assessed between 2000 and 2011 showed lithium go from being the most commonly prescribed drug to the least (Kessing et al, 2015). Similar findings were also found in a separate study carried out in Sweden with the number of lithium prescriptions dropping between 2007 and 2013, which begs the question, why are we scared to prescribe lithium?

In a recent study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, Lyall and colleagues (2019) seek to ascertain whether similar trends are also seen in the UK over recent years. They used a health informatics approach and conducted a study looking into Scotland’s prescribing patterns for bipolar disorder between 2009 and 2016.

NICE guidance recommends lithium as a first line treatment for bipolar disorder, but it remains under-prescribed, perhaps because patients taking the drug require careful monitoring via blood tests, or possibly because other medications are more strongly marketed by pharmaceutical companies.

Methods

Lyall et al employed a data linkage approach to help analyse and elicit trends for prescribing in bipolar disorder patients in Scotland between 2009 and 2016. Using the electronic Scottish Mortality Records (SMR), they identified a cohort of 23,135 patients with bipolar disorder who were prescribed psychotropic medication.

All patients in this cohort were linked to the PIS (Prescribing Information System) and so one could determine what drugs were prescribed. The research team then examined trends in patients prescribed in 6 drug categories:

- Mood stabilisers (lithium and valproate)

- Antipsychotics

- Anti-epileptics

- Hypnotics

- Anxiolytics

- Antidepressants.

Random effect logistics model were used and prescribing patterns for lithium and valproate were also examined separately. Valproate was considered potentially interesting in light of recent guidelines surrounding valproate’s teratogenic risk.

Inclusion criteria

- ICD diagnosis consistent with Bipolar Disorder Type I

- An individual must have been consistently prescribed the same medication for a minimum period of 3 months in the year of interest

- The individual received at least 4 prescriptions of the same drug category within a year.

Exclusion criteria

- A diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder Type II or unspecified bipolar disorder

- If an individual’s earliest Scottish Mortality Record of bipolar disorder was during or after the year of interest

- Death was during or before the year of interest.

Results

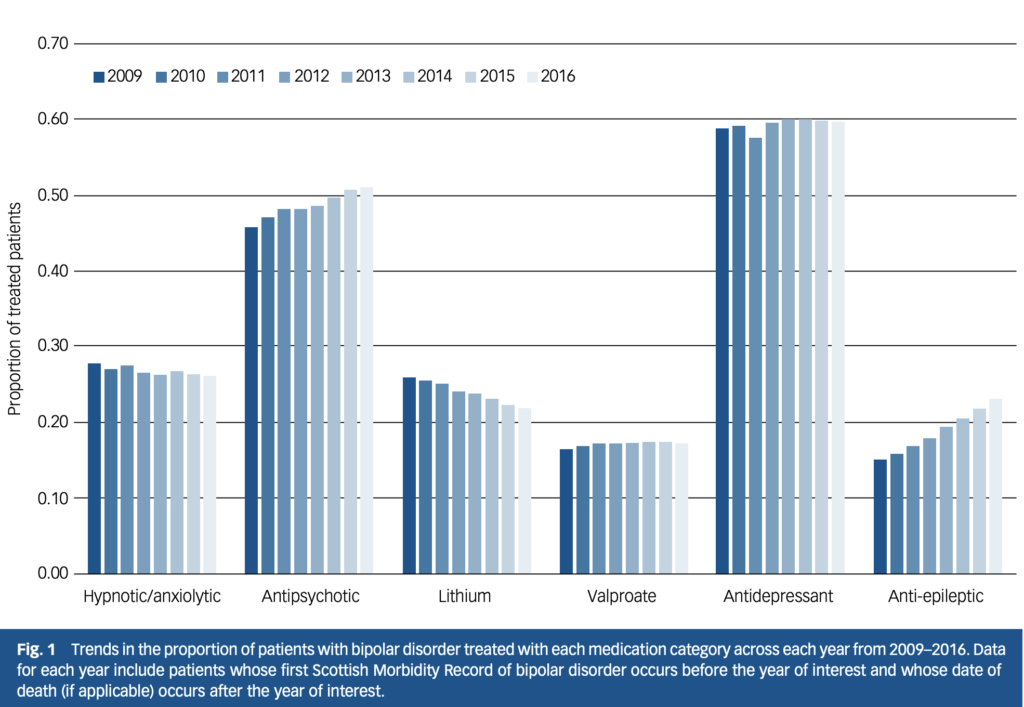

Initial results showed that the most common form of treatment used between 2009-2016 was antidepressant monotherapy (24.96%), whereas lithium monotherapy ranked 5th, with only 5.9% of patients receiving this as their treatment.

To examine change in the odds of prescriptions of each drug category across the years of interest, adjusted for available sociodemographic characteristics, random effects logistic models with standard errors clustered by patient. The odds of being prescribed antipsychotics, valproate and anti-epileptics all increased with each advancing year, whereas the odds of treatment with lithium decreased.

Results were also tabulated for valproate prescriptions for women of childbearing age in comparison to men with the same condition of a similar age. The results showed that between 2009-2016, women of childbearing age had decreased odds of being prescribed valproate with each passing year (odds ratio: 0.93, P value<0.001). Men of the same age were at statistically significant increased odds of being treated with valproate (odds ratio 1.11, P value: 0.001).

This Scottish study shows a clear trend towards decreasing lithium use, despite the fact that recent (2014) NICE guidance recommends lithium as a first line treatment for bipolar disorder.

Conclusions

The results show that, over a 7 year period, there has been a decline in prescribing lithium for bipolar disorder in Scotland.

The author’s note:

This low use of lithium and the trend towards decreasing lithium use is in contrast with the most recent NICE guidelines which encourage the first line use of lithium and indeed state that all patients with bipolar disorder should be informed that lithium is the most effective long term treatment.

Interestingly, the results also showed an increase in the use of polypharmacy in the treatment of bipolar disorder, with 26% receiving two classes of psychotropic medication concurrently and 17% receiving three classes concurrently. The decline in lithium prescriptions appears linked with an increase in polypharmacy, though it remains unclear why this is the case. In my time working in psychiatry, I have noticed that individuals with bipolar disorder are very reluctant to start lithium therapy and are in favour of polypharmacy. This is often due to perceived reduced side-effect burden, without fully appreciating that lithium monotherapy can often be more effective than polypharmacy.

The study shows a decrease in the overall proportion of childbearing females receiving valproate for bipolar disorder. This is a reassuring finding that suggests better adherence to treatment guidelines and a greater awareness of the potential risks. This has been highlighted in the British Association of Psychopharmacology guidelines for perinatal medicine, which state that valproate is the only psychotropic that is contraindicated in women of childbearing age when used for psychiatric indications (MacAllister-Williams et al, 2017).

This study shows an increase in the use of polypharmacy in the treatment of bipolar disorder, with 26% of patients receiving two classes of psychotropic medication concurrently and 17% receiving three classes at the same time. Time for a few bars of Bohemian Polypharmacy anyone?

Strengths and limitations

One of the major limitations of this study is that there is no guarantee that those individuals with bipolar disorder, who were sourced from Scottish Morbidity Records, but did not have any record on the Prescribing Information System (PIS), was actually still a Scottish resident. Individuals who did not have a prescription record on PIS may be receiving medication privately and not from the Scottish NHS or they may in fact have died. This will mean individuals can be lost in follow up and in turn will skew the results in way of either increasing or decreasing the number of lithium prescriptions during the given timeframe.

Crucially the study was not designed to determine why rates were changing and which factors were altering prescribing habits? We wondered about doctor’s habits and patient choice. For all the benefits that lithium is known to have, with the aid of wider available resources such as patient forums and other digital information, individuals are becoming increasingly aware of the side effect burden that lithium carries. As a result, many may be less inclined to agree to start lithium. This may be amplified by the burden of regular blood tests. Recent data from a study carried out in England shows that adequate monitoring has also declined, inferentially supporting such a hypothesis.

Another limitation is the reliance on clinicians’ accuracy in coding bipolar disorder correctly. Misidentification, either through administrative or diagnostic error, can affect the treatment regime indicated/necessity for lithium treatment.

Bipolar disorder patients may not want to start taking lithium because of the potential side effects and regular blood tests, even though it may be the most effective treatment for them.

Implications for practice

Whilst the use of lithium in bipolar disorder might not be straightforward (side effect profile, blood tests etc), the results show a worrying trend that highlights clinicians are steering away from evidence-based guidance, which begs the question why?

There appears to be an educational imperative to reaffirm the evidence base to clinicians and patients, and to see which factors are impacting decision making. There has been a huge emphasis placed on patient choice in recent years, shifting away from previous traditional paternalistic approach to patient care. This in turn can account for patients opting out of using lithium in favour of alternatives. Of concern, lithium is ‘off patent’ meaning it gets almost no promotion, unlike the alternative treatments from pharmacological industries which may sway treatment preferences.

Incidentally, for those of you asking: “What about SIGN guidance? This is a Scottish study after all!” The SIGN guideline for Bipolar Affective Disorder (guideline number 82) was published in 2005 and withdrawn by SIGN in 2015.

In conclusion, although NICE guidance (2014) states that lithium is first line treatment for bipolar disorder, Lyall et al (2019) highlight a trend which is worrying as it suggests there are many people in Scotland are suffering and missing out on optimal treatment. Although the paper suggests that these results may also be representative for England, further research is needed to confirm this. Nonetheless, greater awareness is needed in order to improve our clinical approach to individuals with bipolar disorder using evidence-based treatment options.

This evidence suggests that psychiatrists are steering away from NICE bipolar guidance, which begs the question why?

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Lyall, L., Penades, N., & Smith, D. (2019) Changes in prescribing for bipolar disorder between 2009 and 2016: National-level data linkage study in Scotland. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1-7. doi:10.1192/bjp.2019.16

Other references

Goodwin FK, Jamison KR, Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression (2nd edn). Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kendall T, Morriss R, Mayo-Wilson E, Marcus E; Guideline Development Group of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014) Assessment and management of bipolar disorder: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014 Sep 25;349:g5673. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5673.

NICE (2014) Bipolar disorder: assessment and management. Clinical guideline CG185. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 24 Sep 2014.

Kessing LV, Vradi E, Anderson PK. Nationwide and Population based prescription patterns in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2016; 195: 50-6.

McAllister-Williams, R. H. et al. (2017) British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 31(5), pp. 519–552. doi: 10.1177/0269881117699361.

Photo credits

- Photo by Zach Meaney on Unsplash