Bariatric surgery is generally associated with sustained weight loss and improved physical health for severely obese individuals (Buchwald et al., 2004; Maggard et al., 2005).

Yet, one factor that could influence variation in outcomes is the presence of preoperative and/or postoperative mental health conditions. Evidence suggests that mental health conditions may be more common among patients seeking bariatric surgery than in the general population (Livhits et al., 2012; Müller et al., 2013).

However, the actual prevalence of mental health conditions within this population, their association with postoperative outcomes, and the association between receiving bariatric surgery and the clinical course of mental health conditions, has yet to be firmly established.

Thus, this was the aim of a new meta-analysis led by Dr. Aaron J. Dawes, recently published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) (Dawes et al, 2016).

Methods

The authors searched for English language articles, published between January 1988 and November 2015, relating to the prevalence of mental health conditions in adults seeking and/or receiving bariatric surgery, the associations between preoperative mental health conditions and weight loss after surgery, and the associations between receiving bariatric surgery and the clinical course of mental health conditions.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Study participants had to have a body mass index (BMI) of at least 35.

- Dawes et al. (2016) defined mental health conditions as:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Personality disorders

- Substance abuse disorders

- Suicidality or suicidal ideation

- Eating disorders (principally binge eating disorder).

- All mental health diagnoses had to have been made preoperatively, and studies that asked patients to recall their preoperative mental health status were excluded.

- The presence of mental health conditions needed to have been established using a formal diagnostic method, such as a structured clinical interview, or a diagnostic scale.

Dawes et al.’s (2016) analyses were restricted to:

- Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

- Multi-institutional observational studies

- Single-institution studies with a sample size of at least 200 using random or consecutive sampling

- Single-institution studies with a sample size of at least 500 using nonconsecutive sampling.

Study quality was assessed using an adapted quality assessment tool, with a focus on risk of bias, and the quality of the evidence presented in each study was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria (Balshem et al, 2011). The final sample consisted of 68 articles, 59 of which explored prevalence and 27 of which explored associations (these subgroups were not mutually exclusive).

Results

A meta-analysis of the 68 articles included in the final sample revealed that in terms of the prevalence of mental health diagnoses among adults seeking and/or receiving bariatric surgery:

- The three most common mental health diagnoses were

- Depression (19% [95% CI, 14% to 25%])

- Binge eating disorder (17% [95% CI, 13% to 21%])

- Anxiety (12% [95% CI, 6% to 20%])

- The estimated prevalence of depression (19%) and binge eating disorder (17%) among bariatric surgery patients was greater than the estimated prevalence of depression (8%) and binge eating disorder (1% – 5%) in the US general population.

- Overall, the quality of this evidence was moderate.

In terms of the associations between preoperative mental health conditions and postoperative weight loss, the evidence was inconsistent and low quality for all mental health conditions.

In terms of the associations between receiving bariatric surgery and the clinical course of mental health conditions:

- Depression improved following bariatric surgery in 11 of the 12 studies included in the meta-analysis that reported on changes in the prevalence or severity of depression. The quality of this evidence was moderate.

- Three studies that reported on changes in the prevalence or severity of binge eating disorder found improvement two years after surgery. However, this improvement did not appear to be sustainable beyond this two-year time-point.

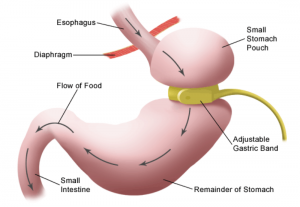

- Three studies reported that rates of alcohol consumption and abuse in patients had increased at up to two years post-surgery, but only when patients had received Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery, as opposed to laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) surgery.

- In general, the evidence was mixed and low quality for all associations between bariatric surgery and the clinical course of all studied mental health conditions, other than depression.

Depression and binge eating disorder were significantly more common in people seeking and/or receiving bariatric surgery, than in the general population.

Conclusions

This study presents a rigorous meta-analysis of the findings in this area relating to three clearly defined research questions.

The authors found moderate-quality evidence that mental health conditions, particularly depression and binge eating disorder, are more prevalent among adults seeking and/or receiving bariatric surgery, than among the general US population.

They also found moderate-quality evidence that receiving bariatric surgery is associated with an improvement in the severity, prevalence, and frequency of patients’ depressive symptoms.

On the other hand, the authors found that patients appear to self-report higher levels of alcohol problems specifically following RYGB surgery. However, they concluded that, overall, further research is needed to provide more substantial evidence of the links between receiving bariatric surgery and the increased risk of alcohol abuse and suicidality in patients.

In line with a previous systematic review (Livhits et al., 2012), the authors also did not find any clear evidence to support their hypothesis that preoperative mental health conditions are associated with differential levels of weight loss after surgery.

Bariatric surgery was consistently associated with postoperative decreases in the prevalence of depression and the severity of depressive symptoms.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this study, which the authors acknowledge, that are important to bear in mind when considering the findings:

- The studies included in this meta-analysis varied in terms of how they measured and defined the mental health conditions that they reported on.

- The articles included in the authors’ final sample may underrepresent the evidence in this area due to publication bias and the authors’ stringent selection criteria, such as the exclusion of small single-institution studies from their final sample, the exclusion of studies in which patients retrospectively recalled their preoperative mental health status, and their inclusion of solely English language articles.

- The generalisability of the results is relatively limited, given that the studies included in this meta-analysis generally tended to report data from single institutions and “as a whole, capture the experiences of fewer than 200 hospitals and outpatient surgery centers performing bariatric surgery around the world” (p. 161).

- Caution should be taken not to assume causal links between seeking and/or receiving bariatric surgery and the prevalence or clinical course of mental health conditions. This is because the evidence as it stands cannot establish any causal relationships.

Implications

Overall, this meta-analysis suggests that there is a need for high quality research to be conducted to further explore the likely inflated prevalence of mental health conditions among bariatric surgery patients, as well as the potential associations between mental health conditions and postoperative outcomes, and receiving bariatric surgery and the clinical course of mental health conditions.

It also seems pertinent for future research in this area to explore the mechanisms or factors that could be behind the increased prevalence of depression and binge eating disorder, in particular, among patients seeking and/or receiving bariatric surgery. Similarly, it would also be important for future research to explore the mechanisms or factors behind the associations between receiving bariatric surgery and improvements in the severity, prevalence, and frequency of patients’ depressive symptoms. For example, as the authors suggest, weight loss as a result of bariatric surgery could be related to a range of other positive changes within the individual that could in turn help to improve their depression, such as improved body image and self-worth. Moreover, receiving a psychological intervention, such as therapy, alongside receiving bariatric surgery could also contribute to improvements in mental health issues, such as depression.

Ultimately, as the authors state:

Although our results should not be interpreted as indicating that surgery is a treatment for depression, severely obese patients with depression may gain psychological benefits in addition to the physical benefits already associated with surgery (p. 161).

Finally, as the authors acknowledge, they did not explore the possible associations between the severity and chronicity of mental health conditions and postoperative outcomes, which could be another important avenue for future research in this area. Although as the authors also note, patients with particularly severe mental health issues may be screened out prior to referral for bariatric surgery and so would be excluded from studies in this area.

We are still searching for the optimal strategy for evaluating patients’ mental health prior to bariatric surgery.

Links

Primary paper

Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, Booth MJ, Miake-Lye I, Beroes JM, Shekelle PG. (2016) Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA.2016;315(2):150-163. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18118. [Abstract]

Other references

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jenson MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. (2004) Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292, 1724 – 1737. [PubMed abstract]

Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, Maglione M, Sugerman HJ, Livingston EH, … Shekelle PG. (2005) Meta-analysis: Surgical treatment of obesity. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142, 547 – 559. [PubMed abstract]

Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, Parikh JA, Dutson E, Mehran A, … Gibbons MM. (2012) Preoperative predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: Systematic review. Obesity Surgery, 22, 70 – 89. [PubMed abstract]

Müller A, Mitchell JE, Sondag C, deZwaan M. (2013) Psychiatric aspects of bariatric surgery. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15, 397. [PubMed abstract]

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Guyatt GH. (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64, 401 – 406. [PubMed abstract]

Bariatric surgery can help improve depression, says new meta-analysis https://t.co/u4JEAZGzPs #MentalHealth https://t.co/TYtyABu6bH

RT iVivekMisra Bariatric surgery can help improve depression, says new meta-analysis https://t.co/20XSzOvyeM #Men… https://t.co/Umbtw4CoGI

Today @em_stape on mental health conditions among patients seeking & undergoing bariatric surgery https://t.co/PxGHD0n0ff

Depression and binge eating disorder are common in people seeking and/or receiving bariatric surgery https://t.co/PxGHD0n0ff

#Bariatric #surgery can help improve #depression https://t.co/rgpVYFNXxm @Mental_Elf examines the #evidence from a #metaanalysis

Bariatric surgery consistently assoc w postoperative decreases in depression prevalence & severity of symptoms https://t.co/PxGHD0n0ff

We’re still searching for the optimal strategy for evaluating patients’ mental health prior to bariatric surgery https://t.co/PxGHD0n0ff

Don’t miss: Bariatric surgery can help improve depression, says new meta-analysis https://t.co/PxGHD0n0ff #EBP