It’s 4 am and your bleep goes off. The number that flashes on the screen is from the main hospital – you know. Before you even dial it in you know what the complaint will be. Sure enough, the on-call doc on the other side of the line is tearing her hair out as there is a patient on the admissions unit wreaking havoc. The patient is hallucinating, and does not know where he is. He will not stay put in his bed. Instead he is running up and down the ward fighting care assistants, pulling drips off other patients and screaming something about the ward being infested with spiders. “He is psychotic! Can you come down here and sort him out?” she asks.

I have been on the receiving end of that phone call quite a few times. You would think I have figured it all out by now; in truth I still dread it. This situation makes for a complex conundrum where you have to carefully balance the needs of your patient, the needs of other patients on the ward and the needs of the non-psychiatric staff that want “something to be done”. When the medic that is calling you says “can you come here and sort him out” what she means is “get him out of my ward and into a psychiatric bed, pronto.” Unfortunately, that is the worst thing you could do for the patient. This state of confusion, reckless behaviour and visual hallucinations is called delirium and it means that the patient has a potentially life-threatening condition; which is not what psychiatric wards are good at dealing with.

Delirium is a state of mental confusion that can happen if you become medically unwell. It is also known as an ‘acute confusional state’.

Your best option at that stage is to advise your colleague to start all the supportive measures we know work very well for delirium, which can be summarised as:

- Do all the medical tests you need to do to find out why the person is delirious and treat that

- Make sure the person eats and drinks well, nurse the person in a quiet, well-lit environment

- Use consistent staff; ideally the same carers and nurses always

- Have plenty of things in the environment that help the person orient himself both in place and time, like calendars, clocks and a window to the outside.

If you know anything about a modern day hospital, that list of things is as achievable as a colony on Mars. Most wards are noisy, confusing, overcrowded and hard to navigate even for people without delirium and you are constantly meeting new staff. That means that you are left with less than great options.

Top of that list is to use some medication to treat the symptoms of delirium. The list of options there tends to start with antipsychotics as delirium kind of shares some symptoms with psychosis. The question is…

Do antipsychotics work in delirium at all, or are we just prescribing them because we feel we “have to do something”?

Karin Neufield and colleagues explore this question in their paper published this year (Neufield et al, 2016). This is a systematic review and meta-analysis looking at whether antipsychotics are any good in the treatment and prevention of delirium.

Methods

They used published and unpublished trials and cohort studies in English only that they found on mainstream databases including ClinicalTrials.gov from 1988 to 2013. They used established methodology for the review. They excluded papers focusing on drug and alcohol withdrawal and paediatric studies. They only included hospital studies and delirium had to be identified with a validated tool. Two authors reviewed, assessed for bias and extracted all data.

Applying this criteria, they ended up with 19 studies, 7 of which focused on prevention of delirium after surgery. For the meta-analysis they calculated odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes (mortality and delirium incidence) and mean or standardised mean difference for continuous outcomes (delirium duration, severity, hospital and intensive care unit length of stay). The authors carried out sensitivity analyses in postoperative prevention studies only, exclusion of studies with high risk of bias, and typical versus atypical antipsychotics, with no changes to their results.

Results

Prevention

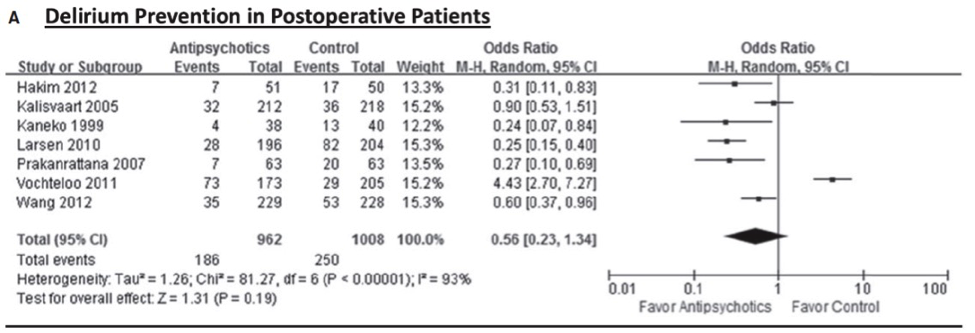

In the studies that specifically looked at prevention of delirium after surgery, there was no significant effect on delirium incidence (OR = 0.56, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.23 to 1.34, I2 = 93%).

If you look at the forest plot in Fig A most of the studies do seem to be on the side of ‘favor antipsychotics’ and you would be justified in wondering what would happen if you took the Prakanrattana study out. The authors performed a sensitivity analysis with just 3 studies at low risk of bias which showed the same results.

Treatment

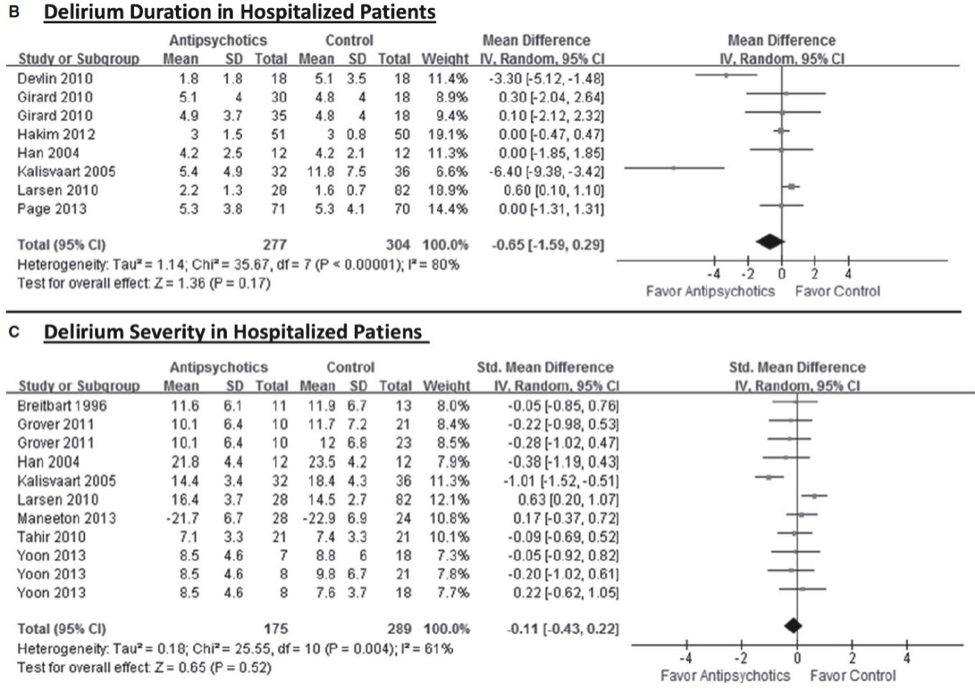

Taking into account all 19 studies, antipsychotic use was not associated with change in delirium duration, severity, or hospital or intensive care unit length of stay. There was high heterogeneity among studies. Figs B and C show the relevant forest plots, which as you can see leave very little doubt.

The authors looked at mortality as well, and found no association.

What is a clinician to do?

The authors conclude that current evidence does not support the use of antipsychotics for prevention or treatment of delirium. They hedge their bets somewhat by saying “additional methodologically rigorous studies using standardised outcome measures are needed.”

Cleverer people than me (read pundits commenting on BMJ Evidence Updates) have put forward these views (I am paraphrasing):

- View 1: “The studies were too different and antipsychotics are all very different, therefore clinicians should not heed the authors’ advice to stop prescribing antipsychotics. Eyeballing the forest plots suggests that there might be a benefit, so let’s go with that.”

I personally do not understand the comment at all. I don’t really think there is any evidence at all to endorse this view. This is important evidence and the comment sounds like “I know better, what should I listen to a bunch of carefully selected and reviewed papers.”

- View 2: “We all know this already but we all still do it. Why does that happen? We need more papers like this to see if we eventually get it through our thick heads and stop doing things just because its tradition.”

Now this view I can get behind. I think that if you look at View 1 you can start to understand why we still do things there is no evidence for. We have done it for the longest time and it is very hard to a) do nothing and b) acknowledge we did the wrong thing all those previous times.

What to do in practice

I still have not answered the question of what to do in practice, so let me try:

- Don’t despair and go see the patient

- Check the diagnosis of delirium is correct

- Be nice to the medics, they are exhausted and scared

- Get the medics to take as close a look at possible at the patient; even if they are scared

- Do go through all the basic nursing care measures, even if you think it is futile. Some of them might be achievable

- Consider the use of antipsychotics in light of the paper. Explain the evidence to the medics

- If you go ahead and prescribe, have a very clear treatment goal that can be measured (frequency of violent incidents, for instance)

- Ask staff on the ward to record whatever indicator you have chosen to assess efficacy

- Prescribe for a limited time only and review efficacy with regards to the target indicator

- Stop the drug if there is no effect on the target indicator

- Stop the drug even if you think there is an effect, as soon as is practical when symptoms resolve (from the review they are likely to have resolved because delirium is resolving not because the antipsychotic has worked)

You may have your own thoughts about how to deal with this situation. If so, do please share them in the comments below.

Links

Primary paper

Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN, Inouye K, Needham DM. (2016) Antipsychotic Medication for Prevention and Treatment of Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 64:705–714, 2016. [Abstract]

@Mental_Elf YES! But, in harmony with all other needs is key to successful treatment.

The delirium conundrum: are antipsychotics a good idea? https://t.co/ZMPeIDZhJN via @sharethis

Today @AndrFon on new SR of #antipsychotics for prevention & treatment of #delirium in hospitalised adults https://t.co/aJxZD7WyQR

The #delirium conundrum: are #antipsychotics a good idea? https://t.co/JxZvWX4fS4 #evidence for a #systematicreview via @Mental_Elf

.@AndrFon struggles to use evidence of antipsychotics for prevention & treatment of delirium https://t.co/aJxZD7WyQR https://t.co/CRFh0Wge5a

Antipsychotics for delirium?

Fab practical clinical advice from @AndrFon

https://t.co/aJxZD7WyQR https://t.co/QpgFXQJj1U

@Mental_Elf @AndrFon the first 3 are so important – “I will see them tomorrow/next week/never” not good enough.

New SR says that current evidence does not support use of #antipsychotics for prevention or treatment of #delirium https://t.co/aJxZD7WyQR

Do antipsychotics work in delirium at all, or are we just prescribing them because we “have to do something”? https://t.co/aJxZD7WyQR

Don’t miss – The #delirium conundrum: are #antipsychotics a good idea? https://t.co/aJxZD7WyQR #EBP

@Mental_Elf #delirium Referendum induced https://t.co/RUbwGGzGDH

@Mental_Elf really good overview and I agree that we are under pressure to do ‘something’ which often means antipsychotics.