There are many nurses working in care homes with nursing. However, it is only recently that there has been concern about whether there are enough nurses willing to work in such care homes or to stay in these jobs. And possible solutions have also highlighted possible further dilemmas, such as the implications of people taking on nursing type roles or exemptions to migration restrictions.

Overall, despite their numbers, care home nurses have been little researched specifically – often lumped together with other care workers. This study explored their occupational roles and occupational status. Here I refer to care homes with nursing as nursing homes for ease of reading and because this is what the authors of this article do.

Method

This article is based on interviews with 13 nurses in north-east England who were working in seven nursing homes of varying size and different types of ownership. The nurses included care home managers and those with other distinct roles such as palliative care nurses and staff nurses.

Each of the nurses was interviewed more than once; some five times. The researchers provide some useful background about the concept of occupational status in the background to the article – that it is usually characterised by possession of authority and recognised knowledge – but that for some groups their status can be undermined if society has an aversion to them. Such aversion could be, for example, that it is ‘dirty work’ that is being undertaken.

Dirt here means dirt but it also includes things that are a bit ‘suspect’ or morally or physically tainted by social ambivalence or distaste for the work or people involved. They also mention debates about occupational status being affected by gender, so that women’s work, for example, even in professions, has lower status.

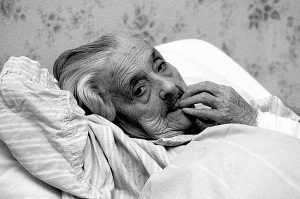

Drawing this together for the present article nursing in long-term care has often been seen as low status with little of the excitement and expertise expected in acute nursing where lives are saved and cures are possible. The authors comment that the complexities and disputes about paying for long-term care in England are likely also to negatively affect perceptions of care home nurses.

The researchers interviewed 12 nurses working in nursing homes in North-East England.

Findings

Those interviewed conveyed a feeling that working as a nurse in a nursing home was of lower status than working in the NHS. They reported that residents’ families and their own social contacts tended not to see them as ‘proper’ nurses and as sceptical about the motives of those working in the commercial care sector.

Several did not really like working in the commercial sector of care, and found dealing with means-testing and charging fees to be morally uncomfortable. The system of public funding of social care was deemed unfair and several thought nursing homes were seen as solely profit orientated.

They thought this affected the way that residents and relatives treated the nursing home staff; a tendency to behave as customers of a service industry; sometimes more assertively than might be expected in healthcare relationships. Not all felt that way but reconciling business and nursing was not easy for many.

Countering these negative images, some of those interviewed thought that they were better able to provide continuity of care for individuals and that care was often of good quality. Some described ways in which they tried to improve their status but the authors suggest that ‘exit’ from the sector is one way in which this is done, thus contributing to the sector’s staffing problems and image.

Another theme arose in relation to social care which is seen as more connected with personal or bodily care (the dirty work referred to in the background) than clinical treatment. Some of those interviewed seemed to suggest that their status was affected by the overall emphasis being on personal care in a nursing home not on clinical skills. Their skills in managing multi-morbidity (several co-existing problems) were under-recognised. Again this contributed to their negative perception of their occupational status. The authors suggest that these influences, of commercialism and ‘dirty work’ (personal care), had greater sway on their occupational status than the female-dominance of their role.

Some nursing home nurses felt uncomfortable that care was subject to charging.

Strength and Limitations

As the authors acknowledge, 13 nurses is not a great number so the findings are possibly not representative. It is not too small for a qualitative study as the interview data were large enough to draw out some themes through analysis. They don’t tell us much about the nurses and don’t compare their interviewees’ characteristics with the wider population of care home nurses’ demographics. They don’t tell us about the multiple interviews, why more than one interview? Was this for practical reasons such as shortage of time or interruptions, or a final chance to go back over earlier responses or to fill in gaps? Interestingly they do note that it was difficult to get interviews – they had to contact 160 homes and only 12 replied to their invitation. This is an important message for other people who want to research in care homes and don’t have money to entice people to take part in research.

Summing up

The care home nursing workforce is large yet relatively unknown. Articles such as these are helpful in presenting their accounts of work and relationships from different positions. Occupational status is also an interesting concept to think about in relation to the care sector and to other professions. For people working with nursing home staff, including regulators, this provides some insight into these nurses’ concerns and feelings.

Links

Primary reference

Thompson J, Cook G, Duschinsky R. What do nursing home nurses in England think about their occupational role and status? Social Theory and Health, August 2016, Volume 14, Issue 3, pp 372-392

Image credits

- Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

- Ulrich Joho, CC BY 2.0

What nursing home nurses in England think about their occupational role and status https://t.co/3qbABjJz6r via @sharethis

What nursing home nurses think of their role and status – read my social care elf about this study https://t.co/tx21xS37Ph via @sharethis

The role and status of nursing in care homes, @JillManthorpe discusses https://t.co/Rys3rsPrcB for @SocialCareElf https://t.co/ockwwzWLp4

Why nurses in care homes often feel devalued, @JillManthorpe discusses https://t.co/ol4cnYgTGV for @SocialCareElf: https://t.co/Hgu5Ggy1Ae

Today’s Elf @scwru blog reports a qualitative study of what nursing home nurses think about their role and status: https://t.co/9TMM98PwLr

Qualitative study: nursing home nurses feel they are regarded as low status workers: https://t.co/9TMM98PwLr

@JillManthorpe Qualitatve study finds that nursing home nurses are uncomfortable with the profit motive in care: https://t.co/9TMM98PwLr

@JillManthorpe Nursing home nurses also felt that their skills were undervalued: https://t.co/9TMM98PwLr

What nursing home nurses in England think abt their occupational role & status – from @JillManthorpe @SocialCareElf https://t.co/ockwwzWLp4

@JillManthorpe The study was based on only 13 interviews. They found it hard to recruit participants. Wonder why? https://t.co/9TMM98PwLr

What nursing home nurses in England think about their occupational role and status https://t.co/hfB5WcpBBF @JillManthorpe @SocialCareElf