Though not a first for the woodland, the elves haven’t reviewed the evidence on mental health service transitions for young people in a while. Today we’re focussing on a recent report that examines the economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK (Knapp et al, 2016).

Young people are at increased risk of mental health problems; the majority of which start in adolescence and persist into adulthood. The impacts are far-reaching, with consequences for educational, social and economic outcomes as well as poor health behaviours that further impact on mental and physical health. It’s also important to take into account the wider impact on friends and family, and the costs associated with health and social care services as well as education and criminal justice costs.

Maybe this is why there hasn’t been much comprehensive research on the impact of youth mental health services – it’s too complicated. This lack of research and understanding might also contribute to the underdiagnosis and unmet need that can be observed for young people with, or at risk of experiencing, mental health problems. In 2004 only 25% of children with mental illness were in treatment; a statistic that did not seem to have improved by 2010. In this new report, Martin Knapp and colleagues seek to address the dearth of findings for broader mental health services for young people, with a focus on economic outcomes.

With budgets cut or frozen, are gaps in provision any wonder?

Methods

The study sought to evaluate the impact of youth mental health services on economic outcomes, and to conduct an economic evaluation of different models of youth mental health care provision. The report is based on several separate studies that use a variety of methods.

1. Literature review

The authors searched 10 electronic databases and tried to identify studies providing evidence relating to economic outcomes associated with youth mental health services.

2. Service mapping

Service mapping was conducted to scope out existing youth mental health services in order to try and identify potential services in which to conduct an economic evaluation. For each service identified, information was collected on the type of service, the provider, the target age group, and any data or evaluations of the service that were available.

3. Analyses of longitudinal data

This is the largest of the sub-studies and more detailed methods and results have been published elsewhere (Knapp et al., 2015; Snell et al., 2013). The authors used data from two national surveys: The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey (BCAMHS) and the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS).

With the BCAMHS data, the authors sought to examine the cost of support for young people with mental health issues and to identify characteristics associated with these costs. 2461 people aged 12-15 were included with baseline, 2 year and 3 year data available. Data on contacts with services were used to calculate costs, which were compared across different mental health issues.

The APMS survey data were used to explore patterns of contact with mental health services and their association with employment, education and training, receipt of benefits and criminal justice contacts.

Results for 16-25 year olds were compared against other age groups.

4. Case studies of local services

Two local services were identified for the purpose of carrying out case studies: the Tower Hamlets Early Detection Service (THEDS) and the Norfolk and Suffolk Specialist Youth Mental Health Service.

THEDS was set up to prevent or delay the onset of psychosis, including provision for people classified as ultra high risk (UHR) of psychosis for two years. For this group, THEDS provided an allocated caseworker, access to psychological therapies, biopsychosocial interventions, family interventions and support. 20 young persons classified as UHR completed two years of treatment, for which pre-, during and post-treatment data were available. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) severity categories were calculated at baseline through to the end of treatment. Employment status was recorded and productivity losses were estimated. Service use costs focussed on A&E visits and hospital admissions from three months pre-baseline, during treatment and after discharge. The cost of THEDS itself was based on caseloads for 100 young people using the treatment programme. The study used a pre-during-post study design with each individual acting as their own control.

The Norfolk and Suffolk service targeted people aged 14-25 years suffering from non-psychotic mental health difficulties. The service facilitated transition and replicated Early Intervention in Psychosis models. Specialist assessment, case management and a range of interventions were offered, with crisis support for those who may otherwise have received inpatient care. Data were obtained from a one year pilot evaluation. A pre-post design was adopted, and the GAF was used to assess mental health status. Social functioning was assessed using the Time Use Survey. Service use data were collected from case notes and interviews from a sample of 214.

The Norfolk and Suffolk evaluation suffered from missing data, though it isn’t explained why.

Results

1. Literature review

The literature review identified 50 studies:

- 13 focussed on the UK

- 35 were designed to evaluate interventions

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) was the most common intervention being evaluated

- Some studies looked at the organisation of care, and most of these considered early intervention programmes.

The authors note a lack of studies focussed on cost-effectiveness.

2. Service mapping

50 services were identified, which varied in terms of treatments, objectives and providers. Whilst some services are emerging, others are closing or changing their focus. Overall, provision is reported to be patchy and often transient. Several services identified at initial mapping had changed or shut down by the time the map was reviewed. As a result, the authors argue that there is no point in mapping services as it would not be an accurate reflection of current provision. Only the THEDS and the Norfolk and Suffolk service collected data that could be used for a modest economic analysis.

Many of the services that were identified changed or were shut down.

3. Analyses of longitudinal data

The BCAMHS revealed that:

- 55% of those with mental health issues at baseline had no contact with services

- Total service use costs were on average £1,778 per young person per year

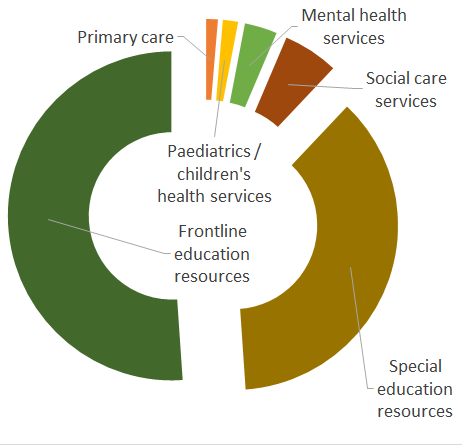

- Education costs far outweighed health care costs, as shown in the figure below

- Young people with hyperkinetic disorders were associated with the highest mean annual costs (£2,780 for 12-15 year olds), followed by conduct disorders (£1,780) and emotional disorders (£1,353)

These results are based on some very small sample sizes.

Distribution of service use costs in BCAMHS.

Looking at the APMS data, the authors found that while younger people experienced similar psychiatric morbidity to adults under 65, a far greater proportion in the older groups used mental health services.

- Between age 16-20, 58% of those with a mental health issue were using mental health services

- Between age 21-25, 36% used services

- Young people with mental health problems were less likely to be in employment, education or training

- Those in receipt of treatment were more likely to be in receipt of benefits.

- Those with mental health issues were 8 times more likely to have contact with the criminal justice system.

4. Case studies of local services

The THEDS sample consisted of 20 young people:

- Most of the sample were from a black and minority ethnic background

- All had a GAF score of less than or equal to 70

- 45% (9) were not receiving any mental health services within the previous three months, despite being at high risk

- 75% (15) showed an improvement in mental health after the two years, while none deteriorated

- Hospital admissions, A&E attendances, unemployment and criminal justice contacts all fell.

The authors estimate a huge (implied) cost difference of £473,120 for the 20 young persons. Approximately 70% of this was associated with a reduction in use of NHS services and most of the rest with productivity gains. The cost of the service was estimated at £106,174 for the 20 young people. As such, THEDS looks promising from both a cost and effectiveness perspective.

The Norfolk and Suffolk service sample included 214 young persons (139 female, 75 male) with an average age of 19 years:

- Average GAF score increased from 46.7 to 59.5

- Half remained in a severe state, whilst the rest moved to an improved category

- GAF score at baseline and the number of hours within the service were predictors of improved mental health functioning at follow up

- Employment and leisure time increased.

The authors conclude that their limited evaluation may demonstrate a role for specialist services in improving mental health and social functioning for young people with mental health needs. They believe this will have savings over both the short and long term.

Specialist services may improve outcomes, if only they would stay open.

Discussion

The one theme that ties together the various facets of this research is the lack of robust data within this research area, and the need for further research. Unfortunately, this study isn’t able to remedy the problem. There are more limitations to the study than we are able to list here; many of which the authors clearly admit. None of the findings should be taken at face value.

The systematic review methodology lacks clarity. The analyses of longitudinal data are not able to tease apart the complex networks of causality between family life, education and mental health. No justification is provided for some of the assumptions adopted by the analyses of the national survey data, including the age bandings used. Despite some apparently large datasets, many of the analyses were based on small samples.

The case studies presented here provide anecdotal evidence that specialist CAMHS services might be effective for certain groups, while also cost saving. But this is an edulcorated representation. The findings are limited by the study design, small samples and missing data, which don’t allow for firm conclusions:

- The analysis of THEDS, for example, estimates savings based on extrapolation of baseline data that may be an unrealistic assumption

- The Norfolk and Suffolk service evaluation does not control for baseline differences, so any effect might be entirely explained by regression to the mean.

This isn’t a criticism of the authors, but of the current lack of good quality data and the funds required to generate it. Randomised trials of specialist services are required before any conclusions can be made about their cost-effectiveness. This ought to be a priority for future research, which may help to hold back the tides of funding cuts.

Closed services leave young people stranded without support.

The failure of the service mapping study demonstrates how funding cuts have left CAMHS services in flux. Each part of the study reiterates the poor coverage and unmet need for young people with mental health issues, and this is perhaps its most important message. Many young people could benefit from high quality care (or any care at all), but are being failed by the system.

There are also important implications for future research. The majority of the costs associated with mental health problems in young people lay within the educational cost component. This represents a challenge for commissioners working with health budgets. It also emphasises the importance of capturing the wider impacts of interventions within economic evaluation and the importance of identifying which sectors and providers costs are likely to fall (Shearer, McCrone, & Romeo, 2016).

Summary

- There is a major gap in service provision for young people with mental health problems, which may in part be due to failures in transition

- Like much research before it, this study was hampered by limitations in the available data

- Future research should focus on the cost-effectiveness of specialist services, with attention paid to the costs falling on the education sector.

Links

Primary paper

Knapp M, Ardino V, Brimblecombe N, Evans-Lacko S, Iemmi V, King D, Snell T (2016) Youth Mental Health: New Economic Evidence. LSE Personal Social Services Research Unit.

Other references

Knapp, M., Snell, T., Healey, A., Guglani, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Fernandez, J.-L., … Ford, T. (2015). How do child and adolescent mental health problems influence public sector costs? Interindividual variations in a nationally representative British sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 56(6). 667-76. [PubMed]

Shearer, J., McCrone, P., & Romeo, R. (2016). Economic Evaluation of Mental Health Interventions: A Guide to Costing Approaches. PharmacoEconomics. [PubMed]

Snell, T., Knapp, M., Healey, A., Guglani, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Fernandez, J.-L., … Ford, T. (2013). Economic impact of childhood psychiatric disorder on public sector services in Britain: estimates from national survey data. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(9), 977–985. [PubMed]

Economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK https://t.co/ojq21IhJXo #MentalHealth https://t.co/3YgURhVrbv

Today @captain_canaway @ChrisSampson87 blog New Economic Evidence on Youth Mental Health @YoungMindsUK @PSSRU_LSE https://t.co/XClYJRMQqc

Today! Major new collaboration w/ @captain_canaway on #healtheconomics of #mentalhealth services for young people https://t.co/CG7jNdR3jZ

Economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK https://t.co/DSg25hUIuS via @sharethis

Economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK

https://t.co/XXAeypSAjy via @sharethis @SPHeREprogramme

Economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK https://t.co/OUXoOSNibH via @sharethis

Recent @PSSRU_LSE evaluation of 2 models of youth mental health service provision https://t.co/XClYJRMQqc #CAMHS https://t.co/XMMRPk21E2

Economic impact of youth #mentalhealth services in the UK https://t.co/SNNmpYkrRk @Mental_Elf looks at the #evidence for different models

Economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK https://t.co/vOsNPZAeGG

Economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK https://t.co/xAYKuU14YK

Me and @ChrisSampson87 digest a 120 page report on #mentalhealth and economics into a palatable size portion: https://t.co/o8isMPrZju

Don’t miss: Economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK https://t.co/XClYJRMQqc #EBP

Economic impact of youth mental health services in the uk

Looks to be worth a read

https://t.co/mCimPiU179 https://t.co/6LBQtcIK9A

RT @Mental_Elf : #Economic impact of #youth #mentalhealth #services in the #UK https://t.co/unYFErV931 via @captain_canaway

[…] Read the full analysis here […]

[…] Read the full analysis here […]

https://t.co/rGf3Z32kBH @ourhealthiersel @MaudsleyNHS @AnneRainsberry @rowlandmarc @NikkiKF @baggaley_m #Hugeopportunity 4 C&YP, SE London

[…] Economic impact of youth mental health services in the UK. Alastair Canaway and Chris Sampson blogged about an LSE review, which highlights the major gap in service provision for young people with mental health problems, which may in part be due to failures in transition. Like much research before it, this study was hampered by limitations in the available data. Future research should focus on the cost-effectiveness of specialist services, with attention paid to the costs falling on the education sector. […]