The figures for self-harm in adolescents range from 10-14% (Hawton, Rodham, Evans & Weatherall, 2002; O’Connor, Rasmussen, Miles & Hawton, 2009).

The term ‘self-harm’, widely employed in the UK and in Europe, refers to ‘self-injury or self-poisoning, irrespective of the apparent purpose of the act’ (NICE, 2004; 2011), meaning that harming oneself with or without the intention to die is called self-harm. It is worth noting that this is different from the US definition of ‘non-suicidal self-injury’ or ‘NSSI’ which specifically excludes self-poisoning (taking an overdose or swallowing chemicals) and behaviours where the person has not carried them out with the intention of dying. This is a topic of fierce debate within the suicide research community and a full discussion of this can be found in Kapur, Cooper, O’Connor and Hawton (2013) and Butler and Malone (2013).

Many individuals who self-harm are young people, and self-harm is disproportionately higher in females than males (Bickley et al., 2013; Hawton et al., 2012). The media is frequently awash with stories of rising self-harm in teenagers, but behind the numbers are individuals and families who are trying to navigate their way through the highly complex array of feelings that come with being the person experiencing severe emotional distress, and being the ones playing a supportive role to young people who are in acute psychological pain.

With this in mind, it is perhaps surprising that there has been so little research attention directed to the impact of young people’s self-harm upon their families. A recent BMJ Open paper by Anne Ferrey et al., (2015) used in-depth qualitative interviews to explore the experiences of parents and families (siblings as well as extended family, e.g. grandparents) in relation to their son or daughter’s self-harm.

Behind the statistics are individuals and families trying to navigate their way through severe emotional distress, and supporting a loved one in psychological pain.

Methods

Through “mental health charities, support groups, clinicians, advertisements, social media, personal contacts and snowballing through existing contacts”, the study recruited 37 parents of young people who had self-harmed. Introductory information was passed on to those who expressed an interest in taking part in the study, who then had the chance to further discuss the study with the researchers via phone/email. A mutually convenient location was then selected for the interview to take place, which took on average, around 1 hour 24 minutes.

The interviews were “semistructured narrative interviews”, so participants were first asked to talk uninterrupted about their experiences around supporting their child who self-harmed. Based upon things the participant had said, follow up questions were asked by the interviewer in order to elicit more information. Further ‘semistructured prompts’ were used, i.e. questions that were specific to particular points of interest, but also allowed participants to give extra information and not stick rigidly to the question, as is often the case with natural conversation. These prompts had been generated from relevant topic areas identified from a literature search, and also the input of a project Advisory Panel (made up of ‘parents, researchers and clinicians’).

All interviews were recorded and then transcribed by professional transcribers. Prior to providing consent for their interviews to be used in the study, participants were able to view and edit their interview transcripts. The final transcripts were coded according to a framework developed using constant comparison methods: themes that surface in the data are incorporated with themes the researcher anticipated would be present in the data. Broad themes were pinpointed around all of the topics discussed by participants, then the researchers engaged in detailed close analysis of the themes specific to how young people’s self-harm had impacted upon their parents and families.

Results

Self-harm had a significant impact upon parents and families across many different areas of their life, at home, school, and work, but good support and information mitigated negative effects.

The main ways that young people’s self-harm impacted upon parents and families were:

- Stress and anxiety for parents; worrying they had ‘done something wrong’ or ‘failed’ their child

- Parental relationship difficulties with partners, extended family, and their other children

- Conflicting emotions for siblings; frustrated at amount of attention parents spent on their sibling who self-harmed, wanting to help support their brother/sister

- Siblings worrying that their usual teasing and bickering with their brother/sister will cause them to self-harm

- Financial worries from disrupted employment or having to travel long distances to visit their child in hospital

- Social isolation

The main things that helped parents and families with supporting their child who self-harmed were:

- Receiving information about self-harm

- Hearing about the experiences of other families

- Contact with other parents of children who self-harmed

- Flexibility and understanding from employers in relation to having to take time off, frequently at short notice

- Non-judgmental treatment by school, clinical, and other support services

Conclusions

Within the study sample, supporting a child who was engaging in self-harm behaviour had an impact upon many different areas of life for parents and families. Parents and siblings often blamed themselves, and felt ashamed to speak to others about their child’s self-harm because of stigmatised attitudes (real and perceived) from schools and healthcare professionals. A non-judgmental approach from others, being able to get information about self-harm, and to speak to other families who shared similar experiences, were all factors that mitigated parental and family stress.

Self-harm by young people has a major impact on parents and other family members.

Strengths and limitations

This important and timely study throws into sharp relief some of the very real concerns of parents and families around their child’s self-harm, and what they have observed the worries of their other children to be around this. The qualitative methodology has allowed for a fuller and more nuanced approach to enable a better understanding of a range of issues around supporting young people who are experiencing severe emotional pain and are self-harming.

It is a widely acknowledged fact that young people who present to hospital with self-harm are only a small proportion of the young people who are engaging in self-harm behaviour (Hawton, Rodham, Evans & Harriss, 2009). By recruiting participants for the study from a range of sources, including mental health organisations and social media, it means that the study has a greater likelihood of including a more diverse group of individuals than had it solely relied upon recruiting from children’s hospital presentations; this is further evidenced by the range in type and severity of children’s self-harm behaviours reported by parents taking part in the study.

All but one of the parents interviewed was from a White ethnic background, and Black and Ethnic Minority families may have fundamentally different experiences of self-harm that could not be explored within this study due to lack of ethnic diversity within the sample. We know little about this, and it should be an important area of focus for future research.

Something which could perhaps have benefited from even more emphasis within the paper, are the stories about what worked. What helped parents to feel in a better position to support their child, their partner, and their other children through what can be a period of highly charged emotional turbulence, for everyone involved?

For many of the parents, the interview took place a number of years after their child had first started self-harming, thus their retrospective accounts of their experiences may be different to those of parents who were interviewed closer to the time their child began to harm themselves.

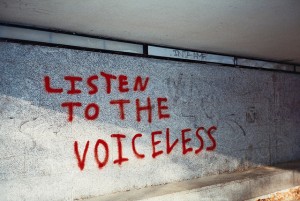

Against a backdrop of some notable controversies regarding the value of qualitative vs. quantitative research (see Greenhalgh et al; 2016; Hjemeland & Knizek, 2010; Krumholz, Bradley & Currie, 2013), this qualitative paper provides a critical platform for the voices of parents and families of young people who self-harm, for whom percentages and p-values alone do not necessarily provide a fully adequate vehicle for telling their stories.

This study highlights the very real impact of self-harm upon parents and families. It also draws attention to many action points of vital practical significance for clinicians, schools and other support services to address, namely that parents and families are better able to support their child or sibling who self-harms when those around the family provide a supportive, non-judgmental, and compassionate environment.

Professionals can best help parents and families by providing a supportive, non-judgmental and compassionate environment in which they can best help their child or sibling who self-harms.

Summary

- Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 37 parents of young people who had self-harmed, to find out how this had impacted upon their family life.

- The findings revealed that many parents felt their child’s self-harm had put pressure on family life by causing emotional, familial, and financial strain.

- Parents and siblings often felt they had done something wrong which had caused their child/sibling to self-harm.

- Access to information and non-judgmental support from services, friends and extended family, helped parents to cope with their feelings around their child’s self-harm.

- Understanding and flexibility from employers was also beneficial in helping parents to manage the practicalities of needing to be there for their child who was experiencing distress.

This excellent study illustrates why qualitative research is so important in mental health.

If you need help

If you need help and support now and you live in the UK or the Republic of Ireland, please call the Samaritans on 116 123.

If you live elsewhere, we recommend finding a local Crisis Centre on the IASP website.

We also highly recommend that you visit the Connecting with People: Staying Safe resource.

Links

Primary paper

Ferrey AE, Hughes ND, Simkin S, Locock L, Stewart A, Kapur N, Hawton K. (2016) The impact of self-harm by young people on parents and families: a qualitative study. BMJ Open, 6(1), e009631. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009631

Other references

Bickley, H., Steeg, S., Turnbull, P., Haigh, M., Donaldson, I., Matthews, V., … Cooper, J. (2013). Self-Harm in Manchester January 2010- December 2011 (PDF).

Butler, A. M., & Malone, K. (2013). Attempted suicide v. non-suicidal self-injury: behaviour, syndrome or diagnosis? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(5), 324–325.

Greenhalgh, T., Annandale, E., Ashcroft, R., Barlow, J., Black, N., Bleakley, A., … Ziebland, S. (2016). An open letter to The BMJ editors on qualitative research. BMJ, i563.

Hawton, K., Bergen, H., Kapur, N., Cooper, J., Steeg, S., Ness, J., & Waters, K. (2012). Repetition of self-harm and suicide following self-harm in children and adolescents: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England: Repetition and suicide after self-harm. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(12), 1212–1219.

Hawton, K., Rodham, K., Evans, E., & Weatherall, R. (2002). Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. BMJ, 325(7374), 1207–1211.

Hawton, K., Rodham, K., Evans, E., & Harriss, L. (2009). Adolescents who self harm: A comparison of those who go to hospital and those who do not. Child And Adolescent Mental Health, 14(1), 24-30. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00485.x

Hjelmeland, H., & Knizek, B. L. (2010). Why we need qualitative research in suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(1), 74–80.

Kapur, N., Cooper, J., O’Connor, R. C., & Hawton, K. (2013). Non-suicidal self-injury v. attempted suicide: new diagnosis or false dichotomy? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(5), 326–328.

Krumholz, H. M., Bradley, E. H., & Curry, L. A. (2013). Promoting Publication of Rigorous Qualitative Research. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 6(2), 133–134.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2004). Self-harm. The short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2011). Self-harm: longer term management.

O’Connor, R. C., Rasmussen, S., Miles, J., & Hawton, K. (2009). Self-harm in adolescents: self-report survey in schools in Scotland. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(1), 68–72.

RT iVivekMisra Self-harm in young people: how can we support parents and families? https://t.co/OOZ8l7rtSf #Menta… https://t.co/czS6lvyIYQ

RT @Mental_Elf: Today @LivveyKirtley on qualitative @BMJ_Open study about impact of self-harm by young people on parents & families https:/…

Morning @dr_adventurer We’ve blogged about your self-harm in young people study https://t.co/5GsQfMHU5r Please let us know your thoughts

@Mental_Elf Thanks for highlighting our research! Free research-based Guide for Parents also available at https://t.co/jja1JAIxd0

The impact of #selfharm by young people on their parents & families. Me for @Mental_Elf on new @BMJ_Open paper: https://t.co/Leyw1XrbDT

RT @TweetMRS: Here’s @Mental_Elf on why qualitative research is so important to mental health: https://t.co/oRVwY1hFjK

RT @Mental_Elf: Why is #qualitative research so important in mental health?

Here’s why https://t.co/DAgkq17MrE

#SelfHarm https://t.co/RkJSn…

Self-harm by young people has a major impact on parents and other family members https://t.co/5GsQfMHU5r

RT @Mental_Elf: Don’t miss – Self-harm in young people: how can we support parents and families? https://t.co/5GsQfMHU5r #EBP #EDAW16

RT @LivveyKirtley: Qual study helps tell the stories behind the numbers abt impact of children’s #selfharm on family: https://t.co/Q1QYPDGL…

RT @Mental_Elf: Parents/families of children who self-harm need non-judgmental support & compassion from professionals https://t.co/5GsQfMH…

Self-harm in young people: how can we support parents and families? https://t.co/URXmEFIFfj via sharethis

What impact does a young person’s #self-harm have upon parents and families? @Mental_Elf https://t.co/JdGriXl1Nl https://t.co/R6TvNV4tiy

Self-harm in young people: supporting parents and families https://t.co/SVIyQuWH1x #rvsed #nssi #parenting

[…] 1Self-harm in young people: supporting parents and families […]

Self-harm in young people: how can we support parents and families? https://t.co/XN6iBMuxjx via @sharethis

Interesting new qualitative study RT Self-harm in young people: how can we support parents and families? https://t.co/9sIeo91WzE

RT @iVivekMisra: Self-harm in young people: how can we support parents and families? https://t.co/0FDWsJTUeD #MentalHealth https://t.co/kbk…

[…] How to support parents and families of (young) people who harm themselves? The Mental Elf 2016_03_07 > LINK […]